Marine Protected Areas (MPA)

➡️ MARINE PROTECTED AREAS (MPA) - Rewilding Our Waters

MPAs are designed to protect threatened habitats and boost dwindling biodiversity in our struggling oceans. With the recent ratification of the High Seas Treaty, MPAs have been thrust into the spotlight as a powerful tool for legally regulating harmful human activities such as bottom trawling, overfishing, resource exploitation, and seabed mining.

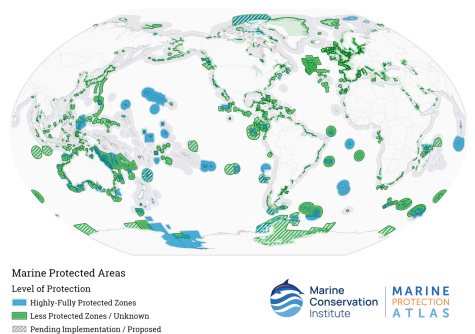

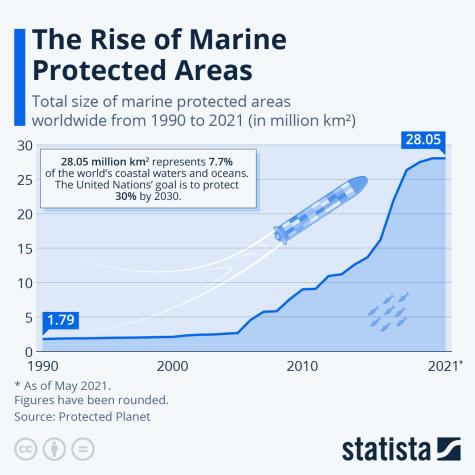

As of 2025, there are over 15,000 MPAs around the world covering roughly 8% of the world's oceans. For these sites to be truly effective, they must be adequately monitored and managed. Of all the MPAs, only 2.9-3.6% are categorised as "fully or highly protected".

Historically weak legislation, inadequate regulations, and poor enforcement have hampered their effectiveness. As of January 17, 2026, we now have the first legally binding framework to protect the wild west of international waters.

Officially called the Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction Agreement (BBNJ), the high seas are international waters that fall outside any nation's jurisdiction, making them rife with unchecked fishing, pollution, and other environmentally destructive activities.

In addition to protecting marine life, another important reason to protect our blue planet is to prevent the release of billions of tonnes of sequestered carbon into the atmosphere. Absorbing 25-30% of human-caused carbon dioxide every year, our oceans are Earth's largest carbon sink.

Jump straight to our resources on ➡️ MAPs

Explore our comprehensive guides on -

- Our Guide to Water & Oceans

- The High Seas Treaty

- Ocean Protection

- The Ocean Plastics Crisis

- Biodiversity Loss

- The Fishing Industry & Overexploitation

- The Shipping Industry

- Deep Sea Mining

MPA Success Stories

Designating MPAs only goes so far strong or full protections that are longstanding and enforced ensure that our efforts are meaningful. Below we list some examples of what carefully managed MPAs can achieve -

-

The Great Barrier Reef (Australia) - Proven healthier ecosystems in protected zones, areas with strict "no-take" zones have higher coral cover, a greater abundance of fish, and improved ecosystem resilience.

-

Cabo Pulmo (Mexico) - Experienced a 463% increase in fish biomass and 1000% increase in marine predators over 10 years. The restored ecosystem has boosted both local tourism and their fishing industry.

-

Gabon (Central Africa) - The first Central African nation to establish MPAs. The protected areas cover ten marine parks over 18,000 square miles, which are home to 20 species of whales and dolphins, the world's largest breeding leatherback turtle population, and 20 species of sharks and rays, many of which are threatened.

-

French Polynesia (South Pacific) - The world's largest MPA was announced in June 2025, covering almost 2 million square miles. The area encompasses their entire Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), protecting marine biodiversity from deep-sea mining and industrial fishing.

Types of Protected Areas

- Marine Conservation Zones (MCZs): Designated areas within UK territorial and offshore waters. There are currently 91 MCZs, and they form part of the wider international MPA network.

- Highly Protected Marine Areas (HPMAs): This designation is reserved for highly sensitive areas. It bans all extractive and destructive human activities. Examples of this are the Ross Sea Region in Antarctica and Tainui Atea in French Polynesia.

- Special Areas of Conservation (SACs) and Special Protection Areas (SPAs): For use within the European Union. Under the Habitats Directive, these areas protect threatened or rare species, habitats with special ecological significance, especially vulnerable areas, or areas critical for carbon sequestration.

- No-Take Zones (NTZs): Areas where all extractive activities are prohibited, allowing for the full recovery of ecosystems and fish stocks. This is the highest level of MPA. Examples include the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park, the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary in California, Ascension Island in the South Atlantic, and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands in the Southern Ocean. No-take areas now cover more than 33% of the MPA.

How do MAPs Work?

- Legal Designation - The area is defined, legally recognised, and geographically mapped.

- Conservation - Goals are set, including the protection of biodiversity, habitats, species, or other defining features.

- Regulation - Restrictions on human activities are put in place.

- Monitoring & Enforcement - Ecosystem health and adherence to restrictions are carefully tracked to ensure compliance and progress.

- Networking - Individual sites can be connected to support migration, resilience, and have a broader impact.

- Local Involvement - Involve local stakeholders at all stages to balance economic, social, and conservation goals. Local knowledge and support are invaluable.

The 30 by 30 Goal

Agreed upon at the 2022 COP15 UN Biodiversity Summit, the 30 by 30 goal is the largest conservation initiative to date. This legally binding commitment aims to halt biodiversity loss and combat climate change by protecting and conserving at least 30% of the world's land and seas by 2030.

In December 2022, 196 countries adopted the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), which includes 23 targets to reverse habitat and species loss. The 30 by 30 goal is one of these targets.

Despite initial promise, the world is off track to meet the goal. Currently, only 8.4% of ocean and coastal areas are protected and conserved. This leaves an area larger than the Indian Ocean to be designated in just 4 years.

The 2024 Protected Planet Report was the first official evaluation of global progress. It identified that the strongest breakthroughs had occurred in the ocean, but the vast majority were in national waters. Coverage in international waters remains very low, at 11%. The newly ratified High Seas Treaty should change this.

Of note, the U.S. is not a party to the GBF, as it is not a part of the Convention on Biological Diversity. This convention was established 30 years ago at the Rio Earth Summit and has never been ratified by the U.S., leaving it as a mere bystander in our global fight against biodiversity loss.

*****

While monitoring and data are still largely insufficient to measure progress, and governmental regulation is uneven, the success of MAPs on a global scale remains challenging.

Technologies such as AI and environmental DNA are increasingly used to monitor site conditions, and the High Seas Treaty has expanded the scope for MPAs beyond national jurisdictions. There are reasons for hope, and MPAs, if implemented and managed correctly, have given our oceans a chance to recover naturally before it is too late.

With 37.7% of fish stocks overfished, more than 12 million metric tons of plastic entering our oceans every year, and ocean acidity 30% higher than pre-industrial times, the time for action is now.

"If we save the sea, we save our world" - Sir David Attenborough

Author: Rachael Mellor, 27.01.26 licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

For further reading on MAPs see below ⬇️

- Marine Protected Area - National Geographic258177

- The Importance of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs) - National Geographic258178

- Gov.uk - Marine Protected Areas (MPAs)507746

- Marine Protection Atlas507749

- Marine Conservation Society507747

- UNEP - Promoting Effective Marine Protected Areas507751

- JNCC - Special Areas of Conservation (SACs)507802

- National Geographic - No-Take Zone507804

- The Wildlife Trusts507748

- Wildlife Trusts - Highly Protected Marine Areas507752

- The Wildlife Trusts - Marine Protected Areas in England507801

- MPA Guide - Protected Planet507754

- Marine Protected Areas - NOAA258180

- Where are marine protected areas located? - NOAA258176

- Marine Protected Areas - IUCN258179

- Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources385953

- NBS Hub - Lamlash Bay no-take zone507808

- Marine Protected Area (MPA) - Wikipedia258182

- Marine Protected Area Network - Wikipedia258184

- Marine reserve - Wikipedia258183

- Urban Marine Protected Areas (MPAs): A systematic review of governance, management and human impact - Science Direct 10/25507755

- Maps show the ocean’s getting a lot more protection. The satellite view is not so pretty. - Anthropocene 06.08.25483828

- Success Stories: Marine Protected Areas That Work - Girringi 04.02.25507758

- MPA Success Story : 45 years of good results in conservation and experimentation of new monitoring technologies - MedPan 13.09.24507788

- MPA Success story : Gökova, an example of co-management with small scale fishers to restore the marine ecosystem - Med Pan, 12.03.24507757

- Video: Marine Protected Areas Success Stories: No Trawl No Problem! - Pacific Wild 07.02.24507794

- A tide of change: What we can learn from stories of marine conservation success - Science Direct 19.05.23507793

- High seas treaty: historic deal to protect international waters finally reached at UN - Guardian 05.03.23333302

- No-take zone: an idea whose time has come - WWF 22.12.22507806

- Assessing the effects of no-take zones in a marine protected area spanning two ecoregions and rock substrate types - Frontiers 16.12.22507818

- 92% of the UK’s Marine Protected Areas do not have full protection from destructive fishing - Greenpeace 14.12.22507807

- A no-take zone and partially protected areas are not enough to save the Kattegat cod, but enhance biomass and abundance of the local fish assemblage - IES 10/22507809

- IMPAC 5 - 5th International Marine Protected Areas Congress 9/22258181

- Five pilot no-take zones in English waters - Fishing News 30.06.22507811

- External fishing effort regulates positive effects of no-take marine protected areas - Science Direct 05/22507812

- MPA Success Story : An important network of Marine Areas to protect and promote sustainable development - Med Pan, 2022507756

- Latin American countries join reserves to create vast marine protected area - Guardian 02.11.21259898

- Case study: Belize – Towards Expansion of No-Take Areas in the MPA System - The Commonwealth 30.06.21507759

- Learning and growing together: improving the effectiveness of MPAs needs everyone - Blue Ventures 02.04.20507797

- Marine protected areas - EEA 13/18507750

- Revisiting “Success” and “Failure” of Marine Protected Areas: A Conservation Scientist Perspective - Frontiers 29.06.18507791

- When an MPA works - WWF 10.11.16507760

- 5 Marine Protected Areas Worth Celebrating - Marine Conservation Institute 24.11.14507789

- Marine conservation zone designations in England - Gov.uk 21.11.13507800

- What makes a “successful” marine protected area? The unique context of Hawaii′s fish replenishment areas - Reef Resilience 15.08.13507795

- The many benefits of fully or strictly protected MPAs, also known as “Super MPAs” - Oceana 507753

- Exploring perceptions to improve the outcomes of a marine protected area - Ecology & Society 507799

- No-take zones: A useful management tool? - CEFAS 507805

- Just a designation? The reality of some no-take zones in the ocean - Ocean Oculus507810