Bhoodan Movement (Vinoba)

Explore the Bhoodan Movement (Vinoba) Guide to understand Vinoba Bhave's vision for land redistribution and its impact on rural India.

➡️ The Bhoodan Movement

Baljeet Kaur was almost nearing the completion of her intricate embroidery work on the coarse cotton fabric, as the last rays of the sun painted the dusky Sangrur sky a warm amber—a radiant shade that her freshly embroidered phulkari dupatta shared. The evening that befell was no different from the countless melancholic ones she had endured since the fateful night her husband had passed away. Her husband, who was a small-scale farmer in the Balad Kalan village of Sangrur district in Punjab, was one among the hundreds who fell victim to the stark economic differentiation that plagues Punjab even today. With his passing, the familial legacy of cultivation came to an irrevocable halt. Stories like these abound in the countryside of India’s ‘food bowl’. In recent years, however, these have gone down as mere footnotes in the annals of history, rarely to be noticed again.

Even today, the agricultural and allied sectors continue to play a pivotal role in India’s economy, constituting a herculean 54.6% share of India’s net workforce. Yet farmers possessing less than 2 hectares of land make up an estimated 80% of this labour force. India has witnessed the havoc wrecked by economic differentiation, especially in the agricultural sector, post the Green Revolution of the 60s.

But this reality was not even close to what India witnessed immediately after its independence in 1947. As India was endeavouring to do away with the colonial system of sharecropping largely controlled by the zamindars (large landowners), it proved to be extremely difficult to push through drastic policy changes, as it had the potential of alienating the zamindari class, which wielded considerable political influence in a nascent post-colonial India. The situation soon started getting out of hand as rogue groups of landless and marginal farmers, accompanied by the poor villagers, started to ambush zamindars’ vehicles as they passed through the forested tracts of present-day Telangana. In the mayhem that ensued, one man emerged as the harbinger of peace, who later went on to earn the distinction of being the spiritual heir of Gandhi. Vinoba Bhave, as he was popularly known, travelled to Telangana to broker a truce with the communist-led farmers, and to everyone’s surprise, he was massively successful.

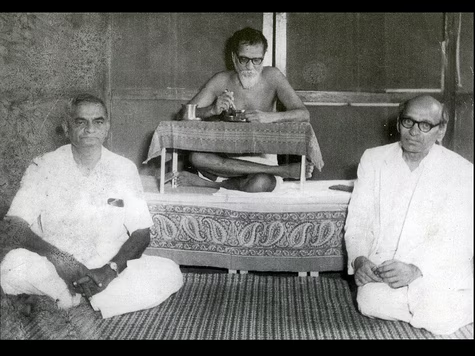

Vinoba—Trustee of the legacy of Gandhi

Christened as Vinayak Bhave, his love for selfless devotion to community welfare blossomed at a delicate age, deeply rooted in the teachings of the Bhagavad Geeta and Upanishads, which he had surrounded himself with growing up. Vinoba exhibited an equal appetite for knowledge when it came to reading the revered writings of some of Maharashtra’s greatest saints and philosophers. As Vinayak grew up, it became clear that he would herald the legacy of Gandhian values across the nation for generations to come.

In 1916, while he was at Kashi (now Varanasi) studying Sanskrit scriptures, motivated by his longstanding desire to attain the all-pervading ‘Brahma’. The news reports about Gandhiji's speech at the newly established Banaras Hindu University caught Vinoba's eye, and he wrote a letter to Gandhi. Vinoba’s devotion to Mahatma Gandhi finally bore fruit when he received the momentous opportunity to meet him in person following an exchange of correspondence through letters. Gandhi was so pleased by his unwavering commitment to the values he had held so dearly that he invited him to come over and stay at his Sabarmati Ashram in Gujarat, where the essence of his teachings could be further shared and lived.

Later, he was asked by Gandhi to take charge of the ashram at Wardha. At Wardha, he sowed the seeds of a weekly newspaper that flourished for the next three years. This weekly started as a Marathi monthly titled ‘Maharashtra Dharma’ and became a melting pot of his deep philosophical musings on the Upanishads. With the inevitable march of time, Vinoba’s journey unfolded like a quiet yet steady river carving its way through the sands of destiny. Something that had started from the Upanishads found utterance in India’s freedom struggle when he proactively participated in Gandhi’s flag Satyagraha in Nagpur and supervised the entry of the ‘Harijans’ (children of God) into the temples at Vykon (Kerala).

But what is Vinoba remembered for today? And why his life and legacy become even more relevant in a situation when not only India but the whole world is plagued by increasing economic differentiation, wrecking financial havoc on demographic groups who are already reeling under the curse of perpetual poverty.

Bhoodan Movement—His Brainchild

The entire nation bore the deep scars of partition in 1947, a wound that cleaved families in two, leaving them adrift on both sides of the border. Vinoba got busy with activities that would assuage the wounds of partition. At the beginning of 1950, he launched the Kanchan-mukti (free from the dependence on gold, i.e., money) and Rishi-kheti (practice of cultivation without the use of bullocks by Indian sages) initiatives.

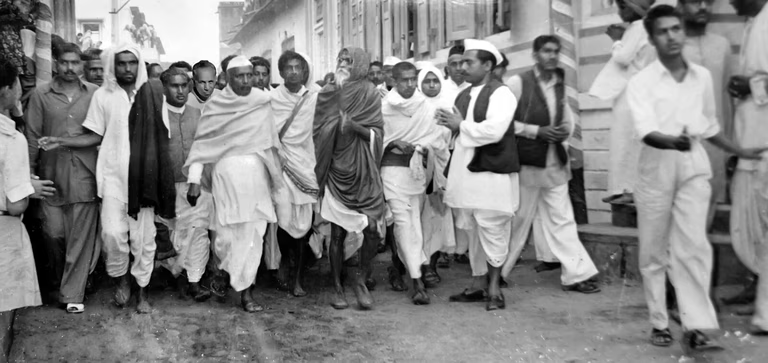

His vision coalesced into a movement that aimed not only to mend but also to restore the soul of a divided nation. It was during this moment of collective despair that the idea of the Bhoodan movement was conceived. The primary and most urgent objective of the Bhoodan movement was the establishment of decentralised independent units where the villagers would determine their affairs themselves. In 1951, after partaking in the Sarvodaya Conference in Shivnampalli, he was bound for Telengana, a region that was bled red by the violent communist rebellion; when Vinoba arrived at the scene with the other Gandhians, they were confronted with a challenge to test their faith amidst rampant violence . Vinoba, on 11th April 1951, declared that en route to Pavana from Shivnampalli, he would tour the communist-infested areas and take stock of the situation, accompanied by his disciples and supporters. On April 17th, at his second stop, Vinoba learnt firsthand that village people were afraid of the police as well as the Communists and that the village was torn along class lines.

It was April 18, 1951, the historic day of the very genesis of the Bhoodan movement (land gift movement), and Vinoba was entering Nalgonda district, the centre of Communist activity. The organisers had Vinoba stay at Pochampalli, a large village with about 700 families, two-thirds of them landless. Pochampalli gave him a warm welcome. Vinoba visited the Harijan colony. By early afternoon, villagers began gathering around Vinoba at his cottage. The Harijans said that they wanted eighty acres of land: forty wet and forty dry for forty families; that would be enough. Vinoba inquired, 'If it is not possible to get land from the government, is there not something villagers themselves could do?' To everyone's surprise, Ram Chandra Reddy, the local landlord, got up and said in a rather excited voice, "I will give you 100 acres for these people.' At his evening prayer meeting, Ram Chandra Reddy reiterated his promise of 100 acres (40 hectares) to the Harijans. This incident, neither planned nor imagined, was the very genesis of the Bhoodan movement, and it made Vinoba ponder that therein lay the potentiality of solving the land problem of India.

The Bhoodan movement gains momentum

The movement went through a number of phases in terms of both momentum and allied programmes. Vinoba was now at the forefront of the movement, which aimed to acquire an estimated fifty million acres of land for the landless from the whole of India by 1957. Over the months, the people of India witnessed how a personal effort took the shape of a mass movement at a time when memories of Gandhi’s mass agitation were fresh. By 1957, donations totalled over 4.5 million acres of land in India.

The Bhoodan movement was an umbrella programme including within its sphere of influence multiple micro-initiatives, such as Sampatti Dan (Wealth Donation) and Shram Dan (Labour Donation) schemes. Economic decentralisation was one of the movement's goals. Vinoba argued that the issue of landlessness needs to be addressed first because it would give a strong base to the economic structure of the village. All must possess land to plough and earn a living. For this, it is that possession of land, property or assets should be acknowledged as Nature's or God's, that a consumer has to do some useful physical work and that the huge disparities between wages or salaries have to disappear. The Bhoodan thus asked the big owners to donate as much land as possible, retaining for themselves only what they need for their self-cultivation; the rich peasants are asked to give one-sixth of their land, and the poor peasants, too, are requested to donate whatever they can as a symbol of their acceptance of the Bhoodan.

It preaches the negation of the desire of "acquisitiveness" or possession of land, believes in the distribution of the means of production among the producers, inspires all to the sentiment of dedication in every activity and insists on the fact that one must be bothered about the well-being of one's starving neighbour as long as he is in misery, urging one to forgo personal happiness until the suffering of others is alleviated. As it is a "Dan" (gift/donation), it argues for the fair and just distribution of land between one and all; it asks the donor of land to fulfil his obligation towards himself and his neighbours; it asserts the right of the landless poor who have been deprived of land due to an immoral economic system, and it demands that all should work on land and none should keep it who does not work.

Gramdan

The concept of Gramdan emerged as a successor to the Bhoodan and was systematically carved out of the learnings of its predecessor. Gramdan, literally meaning 'village gift', tried to accomplish a social revolution through collective community decisions, whereby individual ownership of land was abolished. In Gramdan, all village land was to be pooled and collectively vested in the community. In such a setup, the landless labourers were not subject to acts of charity but were elevated to the status of equals among all other members of the Gramdan community. Vinoba was an ardent believer in the stateless theory; he opined that the Sarvodaya workers believed in the necessity of a stateless society as the immediate goal of this movement. By adopting Gandhi’s ideas to the solution of the basic economic problem of land collection and equitable redistribution among the landless, the campaign became successful in keeping Gandhian principles relevant and even more important after his passing away in 1948.

By 1963, the proponents of the Gramdan movement decided to prioritise three main areas of activity: 1. The nationwide establishment of Gramdan villages, 2. Making these villages self-reliant by establishing khadi and cottage industries. 3. Forming a ‘Shanti Sena’, or peace army, to contain the outbreak of violence in the countryside. With this movement, two new concepts surfaced among the general populace, namely, Buddhidan (gifting intellect) and Jeevandan (the gift of life—dedicating one’s entire life to furthering the cause of this movement).

The Gramdan movement further evolved into Sulabh Gramdan, which drew a clear distinction between ‘ownership’ and ‘possession’. Under this novel concept, almost 95% of all the land donated would remain in possession of the donors. In this way, at least one main aim was achieved: Sulabh Gramdan prevented village land from passing out of the control of the community.

Why is Bhoodan the need of the hour?

Land inequality in the country continues to fuel farmer distress and rural poverty in India. The movement’s emphasis on voluntary land redistribution is a potential blueprint that might hold the key to India’s modern cooperative farming. The reach and impact of the Bhoodan and Gramdan movement were largely felt in the Indian countryside; however, for reforms of land and a fundamental change in the relationship between man and land, attention also has to be paid to urban development and forest rejuvenation.

Time and again, news of illegal land grabbing and encroachment has made it to the headlines in India, and yet, government intervention still remains minimal, if not nonexistent. All the while, the marginal farmers bear the brunt of the crisis head-on. The conventional top-down government reforms, often impeded by weak political will, legal loopholes, and resistance from powerful landowning lobbies, call for an alternative, complementary approach.

Vinoba's larger philosophy of village self-sufficiency, distributive ownership of land, and organic farming is a polemical alternative to the industrial, chemical-based approach of the Green Revolution. He opined that industries only convert 'raw materials' drawn from nature but cannot produce afresh. He further pointed out that only nature is really creative and self-rejuvenating, through interaction with the fresh daily influx of the sun's radiance. Given Vinoba’s philosophy, it is reasonable to reflect that he would have approached the Green Revolution with caution. And then on 15th November, 1982, in silent grace, he embarked on his final journey – the one that he would never return. But left behind a legacy that inspires millions of people even today.

To this day, land fragmentation continues to fuel the unending cycle of poverty, rooted in a credit trap that landless and marginal farmers are often forced into by commercial landowners. Each is a thread, pulling tighter the noose around their weary necks, where dreams of dawn are eclipsed by despair, and the soil demands its due with a life.

The Relevance of Bhoodan Today

In contemporary times, it’s imperative to encourage the culture of trusteeship in corporate and urban environments by urging businesses to contribute shares of profit, unused real estate, or land for public welfare, mirroring the industrial adaptations of trusteeship that characterised the evolution of Bhoodan.

The greatest strength of Bhoodan lies in creating solidarity, empathy, and collective well-being without conflict and coercion. The culture of giving within the movement has abiding relevance today as society faces increasingly widening inequalities, fragmentation of communities, and challenges to rural livelihood.

The local district committees could take the initiative to establish village-level distribution committees and participatory governance structures that could ensure equitable distribution, proper documentation, and training of recipients to avoid the pitfalls of the past through a blend of morality and strong institutions. In times when cynicism about leaders runs deep, Bhoodan's belief in moral suasion and personal example finds new resonance. Youth can learn to find inspiration in leading through service: organising giving circles, voluntary mentorship, time-banking, or even urban-rural skill exchange programs. These nurture a habit of generosity and collective duty.

In essence, the best that Bhoodan can give to today's world is not a blueprint of land reform but rather a call to re-create the heart of our community with compassion, fairness, and a sense of common responsibility. For young people, it is both a legacy to be respected and a living, evolving experiment that demonstrates nonviolent change is possible and necessary.

Recommended Readings :

- Bhoodan Movement - eGyanKosh *.pdf

- Bhoodan Unmasked - Liberation 8/07

- Bhoodan and Gramdan: Are They Relevant Today? - RGICS 9/20

- The Bhoodan Movement - Archive

- The Bhoodan Movement: Vinoba Bhave’s Vision for Land Redistribution - Gandhi and the Contemporary World 2/24

- Bhoodan movement, a unique contribution of Vinoba Bhave - The Hindu 10/22

- Vinoba Bhave’s Bhoodan Movement – How He Made The Rich Donate Their Land To The Landless People - Logical Indian 3/16

- Gramdan Villages in India - International Center for Community Land Trusts

Author: Tanuj Samaddar, 25.09.25, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

For further reading on the Bhoodan Movement see below ⬇️

- YouTube - Bhoodan 18919

- The Bhoodan Movement - Wikipedia 499093

- Bhoodan (Archive) 18920

- Bhoodan-Gramdan Movement - 50 Years: A Review 18921

- Vinoba's Bhoodan Philosophy 18922

- Bhave, Vinoba - Founder of Bhoodan Movement 1951 - Amazon 18923

- Biography of Sahu, Shri Rajni Ranjan 18924

- Krishna Kant, ex-Vice President of India - Wikipedia 18925

- Bhoodan Movement / Gramdan - Wikipedia 18926

- Acharya Vinoba Bhave 488093

- Bhoodan-Gramdan Movement - Acharya Vinoba Bhave 488092

- Sabai Bhoomi Gopal Ki - mkgandhi.org 488096

- Online Book: Sabai Bhumi Gopal Ki (1955) 488095

- Book: Sabai Bhoomi Gopal Ki (Doha) 488094

- Bhoodan-Gramdan Movement: An Overview - mkgandhi.org 488098

- Gramdan Villages in India - International Center for Community Land Trusts 488106

- A village where farms and forests belong to everyone - Menda Lekha 9/24 488107

- Video: Bhoodan Movement | Gramdan Movement | Bloodless Revoution | Vinoba Bhave | Jay Prakash Narayan 1/24 488105

- Gramdan: A Community Ownership 6/23 488100

- Bhoodan-Gramdan Movement - drishtiias 4/23 488101

- The Bhoodan Movement and Land Gifts as Revolutionary Practice - Agrarian Trust 2/23 488103

- Bhoodan and Gramdan: Are They Relevant Today? - RGICS 11.09.20 489412

- The Strangest Social Justice Story This Planet Has Seen - Medium 4/18 488099

- Video: Mendha (Lekha) Documentary on Forest Right 6/12 (in) 488108

- Bhoodan-Gramdan Movement: An Overview - Sevagram Ashram (2011) 488091

- Bhoodan unmasked - Liberation 8/07 488097

- Google Scholar - Bhoodan 488102

- Google Scholar - Gramdan 488104

- Google Images 18927

- Google Search 18928

- Google News 18929